by Katherine Ashe

Theater, in England as in ancient Greece, originally was an expression of religion. Scholars pin the beginning of English theater at about 960 and identify the Quem Queritis as the first play. An Easter presentation, it’s an enactment of the Three Marys coming to Jesus’ tomb and finding the Angel. A priest, dressed in white, sat on the church’s altar as three enactors approached: monks or priests dressed as women, or, in a convent, nuns played the Marys.

Here’s the whole text of the play: “Quem queritis in sepulchro, o Christicolae?” “Whom do you seek, o Christians?” The women respond, “Ihesum Nazarenum crucifixum, o Coelicolae.” “Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified, o Celestial.” He replies, “Non est hic: surrexit sicut preadixerat. Ite, nuntiate quia surrexit de sepulchro.”

“He is not here: He has risen, as he predicted. Go, announce that he has risen from the tomb.”

That’s the whole thing. The play was soon adapted for Christmas, the seekers coming to Christ’s manger. The great popularity of such enactments led to their proliferation, but in the thirteenth century Pope Innocent III banned the clergy from performing or permitting such enactments within the church building itself.

Church performances merely moved to the porches and outer steps or to freestanding stages in public marketplaces, where they were displayed on feast days and performed by honored members of the parish. Interestingly, women seem to have performed the female roles, although, when professional theater developed in the 16th century, female roles were performed by adolescent boys and women were banned from the stage.

Early on these theatricals took two forms, scripted enactments and tableaux or “living pictures.” We know of an Adam and Eve in Paradise tableau from its mention in the Chronica Majora, which tells us that in January, 1236, King Henry III’s wedding procession passed through the play’s Gate of Paradise, complete with nearly naked Adam and Eve greeting him and his bride, and no doubt shivering in the snow. This play apparently was leant to Henry’s festivities by Saint Paul’s Cathedral.

The mouth of Hell was particularly popular, possibly also for its theatrical nudity of both sexes. Somehow the fact that the people don’t move seems to have made nudity in tableaux acceptable.

Separately, the London Guilds began their own forms of theatricals. The guilds, which were religious as well as mercantile and craft organizations, produced plays and tableaux of their patron saints. These, in contrast to the performances belonging to the churches — these last called Mystery Plays — have come to be known as Miracle Plays. Less is know about the early development of the tableaux as they had no scripts and the ledgers that would have recorded their costs probably were lost in the various conflagrations London suffered.

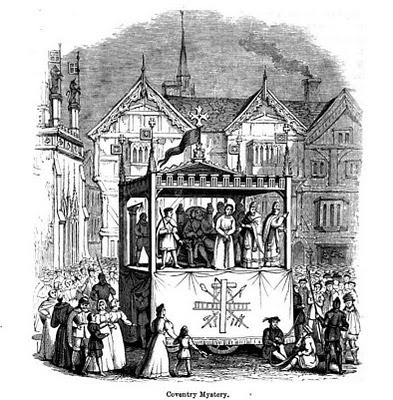

The guilds’ theatricals were mounted on what are now referred to as pageant wagons, which were paraded through city streets during religious festivals. There are abundant illustrations of the later pageant wagons: sometimes quite elaborate vehicles with settings as backdrops for costumed players frozen in poses associated with each guild’s patron saint, or enacting a significant moment in the saint’s life. Occasionally the saint’s “play” was combined with a tableau of the Life of Christ, as in the case of the pageant wagon below, where the Nativity is pictured at the back of the wagon, guilds’ saints at the front and on the sides.

Simultaneous to the flowering of the tableaux were the guilds’ Miracle Plays, centered upon the guilds’ various patron saints.

To name just a few of the subjects: Saint Eligious had begun his career as a goldsmith and was patron of all metalworkers including blacksmiths (possibly one of the side figures above.) The caterers favored Saint Lawrence – because he died on a grill and always was shown being roasted. Saint Apollonoia, who suffered the torture of having her teeth pulled out, was of course the patron of dentists. Here she is, on a temporary stage rather than a wagon. Violence has been popular in theater for a very long time. Simultaneous to the flowering of the tableaux were the guilds’ Miracle Plays, centered upon the guilds’ various patron saints.

As the tableaux were becoming more elaborated, so were the Mystery Plays dealing with scenes from the New Testament. The Coventry cycle consisted of ten plays depicting the life of Christ. Here is a Christ being judged by Pontius Pilate.

The York Cycle apparently consisted of forty-eight plays. The plays continued as popular entertainment during appropriate church holidays until they were banned in the late 16th century.

By then a variety of Mystery Play had developed that suggests a bawdy forerunner of Shakespeare’s scenes designed to appeal to the “groundlings.” The surviving Second Play of the Shepherds of the Wakefield Cycle serves as an example. Here the central characters are a husband and wife, Mac and Gill, who are thieves. Three shepherds come to Mac’s cottage searching for their stolen lamb. Mac tells them his wife has just given birth and mustn’t be disturbed, but the shepherds find their lamb wrapped up as the “new born” in Gill’s cradle. After punishing Mac by tossing him in a blanket, the shepherds return to their flocks, and an angel announces to them the birth of the Savior in Bethlehem. To a modern sensibility this takeoff on the Virgin Birth of the Lamb of God is rather stunning, and perhaps explains in part why the Mystery Plays eventually were closed down.

Note: the pictures included here date from the 15th to the 19th centuries. There are no know illustrations of the early plays.